eOrganic author:

Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming

Introduction

One form of conservation biological control of weeds that appears practical for today's organic farms is conservation of organisms that consume weed seeds, and thereby make withdrawals from the weed seed bank.

Seeds of most plant species can become nourishing food for birds, insects, and other organisms, and weed seeds are no exception. Insects and other organisms consume weed seeds while they are still on the parent plant and after they have been shed. This predispersal predation by specialist insects (species that eat only one kind of weed seed) has been documented in velvetleaf, lambsquarters, pigweeds, and Canada thistle (Kremer and Spencer, 1989; Landis et al., 2005). While these specialists can have substantial impacts on their favorite weed, their utility in protecting crops from multiple weed species may be limited.

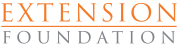

Figure 1. Ground beetles (Carabidae) come in a wide range of shapes, sizes, and colors—and feeding habits. Of the more than 2200 species of carabid beetles known in North America, many are valuable predators of insect pests, and others—like those shown here—are recognized weed seed predators. (a) Anisodactylus rusticus (b) Anisodactylus sanctaecrucis (c) Harpalus affinis (d) Harpalus caliginosus (e) Harpalus erraticus (f) Harpalus pensylvanicus. Photo credits: John Goulet, Canadian Biodiversity Information Center.

Postdispersal weed seed predation has a more widespread impact on weed seed banks. A cleanup crew of insects, other invertebrates, small rodents, and seed-eating birds removes millions of weed seeds from farmers’ fields every year, especially during and in the weeks following weed seed shed. Field studies in North Carolina, Ohio, Iowa , Pennsylvania, Michigan, and elsewhere have documented seed predation rates high enough to reduce current-season inputs to the weed seed bank substantially (Brust and House, 1988; Cardina et al., 1996; Maulsby, 2006; Menalled et al., 2006; Menalled et al., 2007; Westerman et al., 2005; White et al., 2007). Ground beetles (carabids) are among the most widely-documented and consistent weed seed consumers in agroecosysems, but field crickets, ants, earthworms, slugs, field mice, and other small rodents also contribute significantly to weed seed predation. Researchers have documented predation on seeds of many agricultural weeds including common ragweed, pigweed, common lambsquarter, sicklepod, jimsonweed, velvetleaf, fall panicum, and giant foxtail—often at rates high enough to reduce the current season’s input to the seed bank by 80–90 percent or more. Individual predator species show considerable selectivity, with small ground beetles consuming small seeds, and larger insects and rodents preferring larger seeds. However, postdispersal seed predator communities comprised of multiple species can exert an economically important impact on multispecies weed seed banks.

Figure 2. This dusky slug (Arion subfuscus) is one of many species of animals that can contribute significantly to weed seed predation, but may also damage newly emerged crop seedlings. Photo credit: Gary Bernon, USDA APHIS, Bugwood.org.

Microorganisms comprise another set of potential allies against the weed seed bank. Many newly-shed weed seeds are highly resistant to invasion by bacteria or fungi; however, as these seeds age and weather in the soil, their seed coats eventually become more porous, leaving the seeds more vulnerable to microbial attack. Soil fungi contribute to mortality of velvetleaf seeds germinating from a 4-inch depth in the soil (Davis and Renner, 2006), and to the reduction in emergence of corn chamomile and shepherd's purse from soil into which a buckwheat cover crop has been incorporated (Kumar et al., 2008). Several species of pathogenic soil fungi have been found in association with green and giant foxtail seeds in both conventional-till and reduced-till fields in Iowa (Pitty et al., 1987). Naturally-occurring fungi also contribute to mortality in velvetleaf seeds damaged by the scentless plant bug, a specialist predispersal seed predator (Cardina et al., 1996).

Soil microorganisms are believed to play a role in the exponential decline in viability of weed seed populations in the soil (Liebman et al., 2001), but not as much documentation exists for microbial as for macroscopic weed seed consumers. High levels of soil biological activity, such as might occur under intensive organic soil management, or during the weeks following incorporation of a green manure, might shorten the half-life of weed seed banks. However, evidence for a significant role of increased soil microbial activity in reducing weed seed persistence in organically managed fields is as yet inconclusive, and macroscopic predators are currently considered a much larger factor in weed seed mortality than soil microbes (Gallandt, 2003, 2006). Some of the positive effect of high soil quality on weed control may be related to greater crop vigor and competitiveness in well managed soils. More research is needed to estimate the potential for promoting weed seed decay by enhancing soil organic matter and biological activity in vegetable and other cropping systems.

Practical Questions

Can weed seed predation and weed seed decay become viable tools in organic weed management? The answer hinges on several other practical questions:

- Can weed seed consumers remove a significant fraction of the weed seed bank?

- Do weed seed predators also consume crop seeds in sufficient quantities to become problematic?

- What conditions favor the activity of weed seed consumers in agricultural fields?

- What practices can organic farmers implement to optimize the activity of weed seed consumers?

While some weed seed consumers will also take crop seeds, many appear to be sufficiently selective to qualify as predominantly beneficial organisms unlikely to hurt crop establishment or yield. Ground beetles, crickets, and even white footed field mice have been shown to consume many weed seeds without significant impacts on recently sown crops. These seed eaters mostly take seeds that are on or very near the soil surface; crop seeds are commonly planted deep enough to escape predation. Smaller ground beetles that consume small weed seeds like pigweed, lambsquarters, and annual grasses are not physically capable of eating larger crop seeds. On the other hand, slugs can damage tender young vegetable crops as well as eating weed seeds, and crows, blackbirds, and some other seed-eating birds can seriously damage newly-seeded corn and other crops.

Figure 3. The deer mouse, Peromyscus maniculatus, and other small rodents can consume significant numbers of weed seeds from the soil surface. Photo credit: Tom Henthorn, Old Saybrook, CT.

Because weed seed predation activity occurs mainly during and after the annual weed seed return (late summer/early fall), and long after most crops are seeded (spring to midsummer), opportunities exist for weed seed selectivity in time. Noise makers, scare eye bolloons, or other scare tactics can be used to keep birds out of fields during crop establishment, and discontinued later when their services as weed seed predators are desired. Crickets, ground beetles, and ants are most active during the peak weed seed season, and are not as likely to consume small crop seeds direct-sown earlier in the season.

Weed seed predators require suitable conservation and habitat protection in order to remain active in crop fields. Broad spectrum insecticides are likely to wipe out ground beetles and other seed-eating insects. Frequent tillage disrupts ground beetle habitat, and any tillage that inverts or deeply mixes the soil buries weed seeds out of reach of most predators. Seed predators prefer habitat that includes at least some ground cover—organic mulch and/or living vegetation—and ground beetles have shown a clear preference for cover cropped plots over adjacent clean-cultivated plots (Shearin et al, 2008). On the other hand, a really dense or matted mulch may hinder the movement of ground beetles (Menalled et al., 2006). No-till production systems may support higher activity of ground beetles and other seed predators than either organic or conventional systems with regular plowing (Menalled et al., 2007). However, diversified rotations consisting of two years of annual crops with tillage followed by two years under red clover sod enhanced weed seed predation sufficiently to reduce the amount of herbicides and/or cultivation needed for adequate weed control (Westerman et al, 2005). In addition, some seed-eating ground beetles seem to prefer intermediate levels of disturbance over either no-till or moldboard plowing, as long as part of the habitat remains covered by vegetation or mulch (Shearin et al., 2008).

These findings suggest that several organic practices can help conserve ground beetles and other weed seed predators, including cover cropping, mulching, nonuse of broad spectrum insecticides, and crop diversification. Cover cropping appears to be especially important for maintaining habitat for invertebrate weed seed predators (Gallandt, 2006). Additional practices that organic farmers can implement to conserve weed seed predators include reducing tillage, maintaining habitat refuges such as strips of perennial vegetation through the field, and delaying postharvest tillage to give the weed seed cleanup crew a chance to consume the current season’s weed seed crop before it is buried.

Figure 4. Populations of weed seed-eating field crickets, Gryllus pennsylvanicus, reach peak activity later in the growing season, when many small-seeded annual weeds shed their seeds. Photo credit: Edward L. Manigault, Clemson University Donated Collection, Bugwood.org.

While seed predators and soil microorganisms cannot be expected to eliminate weed problems in organic production systems, they can make a significant contribution to seed bank management when integrated with other practices. Based on a considerable body of research, Menalled et al. (2006) concluded that, within a whole-system perspective, “weed seed predation represents a tool that should be integrated with other management practices” for effective ecological weed control. Furthermore, all of the practices that have been suggested for optimizing weed seed predation are consistent with organic production principles and can make economically important contributions to other key objectives, including soil quality, crop health and vigor, and biological insect pest management.

Tips for Enhancing Weed Seed Predation in Organic Vegetable Production

Conservation biocontrol—the practice of protecting and providing habitat for existing natural enemies of weeds and other pests—is the main strategy for promoting weed seed removal by predators and microorganisms. Several specific tactics are available:

- Maintain ground cover with vegetation and/or organic mulch as much of the year as possible in production fields. Interseeding cash crops with clovers or other legumes can enhance predation by crickets and mice (Davis, 2004). Avoid tightly packed organic mulches, which can interfere with ground beetle movement.

- Maintain permanently vegetated field margins or strips through the field to provide permanent habitat for ground beetles and other seed consumers. Planting switchgrass and other native perennials in border areas can enhance ground beetle activity (Davis, 2004) and displace weedy species from field margins.

- Reduce tillage, especially inversion tillage, whenever practical. Strip tillage or ridge tillage can leave seed predator habitat between crop rows; shallow tillage is less disruptive to seed consumers than deep mixing or inversion.

- Avoid or minimize the use of broad spectrum insecticides including botanical sprays like pyrethrum or even insecticidal soap. When such applications become necessary, keep the spray away from ground beetle habitat (e.g., mulched alleys) and spot treat localized pest outbreaks, if practical. Note: in certified organic production systems, insecticides should be used as a last resort only, and the insecticides allowed are limited. For more information, see Can I Use This Input On My Organic Farm?

- Mow weeds promptly after crop harvest to curtail seed formation, but consider delaying tillage to allow seed predators time to consume weed seeds already shed. Postponing tillage until spring maximizes potential weed seed consumption, but may open a niche for winter weeds; waiting a few weeks usually allows for the most intensive period of weed seed predation in early fall.

- Carefully evaluate the tradeoff between delayed postharvest tillage and prompt planting of cover crops after harvest, which may require seedbed preparation. Consider overseeding cover crops into standing vegetables, which eliminates post-harvest tillage and enhances habitat for seed consumers.

- Maintain high levels of soil biological activity and soil quality through appropriate organic matter inputs. Even if this does not significantly accelerate weed seed decay by soil microbes, it will enhance crop vigor and competitiveness against weeds.

This article is part of a series on Twelve Steps Toward Ecological Weed Management in Organic Vegetables. For more on managing the weed seed bank, see:

References and Citations

- Brust, G. E., and G. J. House. 1988. Weed seed destruction by arthropods and rodents in low-input soybean agroecosystems. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 3(1): 19–25. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0889189300002083) (verified 23 March 2010).

- Cardina, J., H. M. Norquay, B. R. Stinner, and D. A. McCartney. 1996. Postdispersal predation of velvetleaf (Abutilon theophrasti) seeds. Weed Science 44: 534–539. (Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4045631) (verified 23 March 2010).

- Davis, A. S. 2004. Managing weed seedbanks throughout the growing season [Online]. New Agriculture Network Vol. 1 No. 2.

- Davis, A. S., and K. A. Renner. 2006. Influence of seed depth and pathogens on fatal germination of velvetleaf (Abutilon theophrasti) and giant foxtail (Setaria faberi). Weed Science 55: 30–35. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1614/W-06-099.1) (verified 23 March 2010).

- Gallandt, E. R. 2003. Soil improving practices for ecological weed management. p 267–284. In Indergit (ed.) Weed biology and management. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordecht, Netherlands.

- Gallandt, E. R. 2006. How can we target the weed seedbank? Weed Science 54: 588–596. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1614/WS-05-063R.1) (verified 23 March 2010).

- Kremer, R. J., and N. R. Spencer. 1989. Impact of a seed-feeding insect and microorganisms on velvetleaf (Abutilon theophrasti) seed viability. Weed Science 37: 211–216. (Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4044846) (verified 23 March 2010).

- Kumar, V., D. C. Brainard, and R. R. Bellinder. 2008. Suppression of Powell amaranth (Amaranthus powellii), shepherd's-purse (Capsella Bursa-pastoris), and corn chamomile (Anthemis arvensis) by buckwheat residues: Role of nitrogen and fungal pathogens. Weed Science 56: 271–280. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1614/WS-07-106.1) (verified 23 March 2010).

- Liebman, M., C. L. Mohler, and C. P. Staver. 2001. Ecological management of agricultural weeds. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Maulsby, D. 2006. Free weed control service: mice [Online]. Rodale Institute. Available at: http://www.newfarm.org/features/2006/0306/weedcontrol/maulsby.shtml (verified 11 March 2010).

- Menalled, F. D., M. Liebman, and K. Renner. 2006. The ecology of weed seed predation in herbaceous crop systems. p 297–327. In H. P. Singh et al. (ed.) Handbook of sustainable weed management. Food Products Press, New York.

- Menalled, F. D., R. G. Smith, J. T. Dauer, and T. B. Fox. 2007. Impact of agricultural management on carabid communities and weed seed predation. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 118: 49–54. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2006.04.011) (verified 23 March 2010).

- Pitty, A., D. W. Staniforth, and L. H. Tiffany. 1987. Fungi associated with caryopses of Setaria species from field-harvested seeds and from soil under two tillage systems. Weed Science 35: 319–323. (Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4044591) (verified 23 March 2010).

- Shearin, A. F., S. C. Reberg-Horton, and E. R. Gallandt. 2008. Cover crop effects on the activity-density of the weed seed predator Harpalus rufipes (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Weed Science 56: 442–450. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1614/WS-07-137.1) (verified 23 March 2010).

- Westerman, P. L., M. Liebman, F. D. Menalled, A. H. Heggenstaller, R. G. Hartzler, and P. M. Dixon. 2005. Are many little hammers effective? Velvetleaf (Abutilon theophrasti) poplution dynamics in two- and four-year crop rotation systems. Weed Science 53: 382–392. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1614/WS-04-130R) (verified 23 March 2010).

- White, S. S., K. A. Renner, F. D. Menalled, and D. A. Landis. 2007. Feeding preferences of weed seed predators and effect on weed emergence. Weed Science 55: 606–612. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1614/WS-06-162.1) (verified 23 March 2010).