eOrganic author:

Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming

Introduction

Weed prevention begins at the planning stage of any cropping system. Plan the crop rotation and cropping system to keep the soil fully occupied by desired living vegetation, or at least covered by organic residues, as much of the year as possible.

An idle soil is the weed devil’s playground! For example, growing continuous corn each summer with winter fallow leaves the entire field available for weeds from harvest in early fall until crop emergence late the following spring. Between-row spaces remain open for weed growth until crop canopy closure—which may take two months or more for corn. This is why continuous corn is economically feasible only for conventional producers who use synthetic herbicides—and many of them now strive to save soil, money, and chemicals by planting a winter rye cover crop after corn harvest.

Any plant or other organism requires a suitable habitat or niche in order to grow and reproduce. A niche is a site within which certain conditions exist, allowing the organism to thrive and complete its life cycle. For most weeds of vegetables and other annual cropping systems, any space or time in which the soil has been recently disturbed or is open and uncovered by other vegetation constitutes a suitable niche. Thus, a key step in ecological weed management is to reduce the number and size of these weed niches in the cropping system.

Most organic vegetable farms grow a diversity of crops throughout the season, and the nonuse of herbicides opens options for crop rotation, multicropping, and cover cropping to limit niches for weeds. However, open niches typically occur during early stages of crop growth (Fig. 1). Those vegetable crops that do not form a solid canopy or root mass pose the greatest challenge, in that they do not fully occupy the niche and are thus most likely to become weedy.

Figure 1. Morning glories and other weeds are just beginning to emerge in the wide expanses of bare soil between these rows of young winter squash. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

A few basic tips for minimizing weed niches include:

- Design tight crop rotations, including production and cover crops that keep fields covered by vegetation as much as possible throughout the calendar year. In regions with cold winters, provide winter cover in the form of dormant hardy cover crops, winter-killed high-biomass covers, or other mulch or crop residues.

- For each field, bed, or section, schedule crop planting to take place promptly after harvesting or terminating the previous crop.

- Schedule a cover crop whenever a field or bed is expected to come out of production for longer than 30 days during the growing season, or for the remainder of the fall and winter (Fig. 2).

- Choose planting patterns—row spacing and within-row spacing—that promote early canopy closure (foliage covers the ground so you can’t see soil surface when viewed from above), without compromising crop yield by crowding.

- When practical, plan to mulch bare soil between crop rows or beds (open niches in space). While mulch does not close off the weed niche as thoroughly as a closed canopy of living crops, it hinders most annual weeds, and conserves moisture and nutrients for the crop.

Figure 2. In the left side of this field, a cover crop of winter rye–hairy vetch was planted promptly after harvest of summer vegetables. Photographed at the beginning of December on a farm on Cape Cod, MA, a thick mat of cover crop has largely closed the niche for winter weeds. On the right, a delay in cover cropping has allowed a mat of common chickweed to grow. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Schedule bare soil periods for limited times only, and only with specific purposes. These could include a period of cultivated fallow to draw down weed seed banks, to weaken invasive perennial weeds, or to germinate and remove weeds in a stale seedbed and allow soil warming before planting a vegetable. Another strategic fallow technique is to mow promptly after vegetable harvest to stop weed seed formation, then delay tillage for a few weeks to give the farm's cleanup crew of ground beetles, crickets, field mice, and other weed seed predators a chance to consume a substantial percentage of any weed seeds formed and shed prior to harvest. In each of these examples, the weed niche has been deliberately opened in a way that facilitates the reduction of weed populations.

Advanced and Experimental Techniques for Closing Off Weed Niches

Innovative growers and researchers continue to explore and develop new ways to reduce niches for weeds. Whereas these methods have not performed consistently enough to be recommended for widespread application, they can give excellent results when used skillfully in certain circumstances. Some of these techniques include:

- Intercropping or companion planting

- Interseeding or overseeding cover crops into established vegetable crops

- No-till cover crop management prior to vegetable planting

- Living mulches—low-growing ground covers between crop rows or beds

- Self-seeding winter annual cover crops

Intercropping

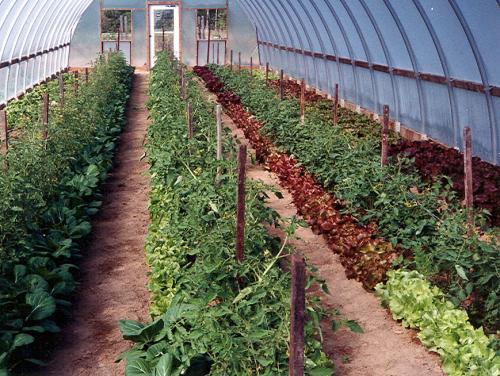

Intercropping is the practice of growing two or more cash crops within a single bed or in alternating rows across the field, to optimize crop use of resources and to minimize space and other resources available to weeds. Vegetable crops grown together should differ in maturity date, plant architecture, rooting depth and structure, and nutrient demands in ways that reduce competition among the crops and increase total competition against weeds. Crop combinations should be chosen that have neutral or positive biochemical interactions with one another—that is, no adverse allelopathic effects—and complementary needs for light, moisture, and nutrients. This practice of companion planting is widely used in ancient traditional food gardening systems, as well as some intensively managed market gardens today.

Examples include: lettuce between rows of tomatoes, in which the lettuce shades out early-emerging weeds, and is harvested before it competes with the tomatoes (Fig. 3); spinach between Brussels sprouts (similar relationship); or quick-growing greens (heavy feeders for N, tolerant of partial shade) between widely spaced trellised rows of tall snow or snap peas, which fix their own N. The Native American “three sisters” system combines corn, runner beans, and squash, whose complementary architecture utilizes space and resources effectively, and usually yields more food per unit area than any one of the crops grown alone. The corn provides support for the beans, the beans fix nitrogen, and the squash vines rapidly cover ground between corn hills or rows and suppress weeds.

Figure 3. Charlie Maloney of Dayspring Farm in Cologne, VA (Tidewater region) intercrops lettuce and bok choy with his high-tunnel tomatoes, thus producing two crops while virtually eliminating niches for weeds in his production beds. The greens are ready to harvest just as the tomatoes enter their rapid growth phase and begin to occupy the whole bed. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Another form of intercropping alternates widely spaced rows of large vegetables like tomatoes or winter squash with swaths of cover crop such as buckwheat. The latter is allowed to grow and suppress weeds for several weeks, then cut before it begins to compete with the vegetables, and left on the soil surface as a mulch that retards later-emerging weeds.

Interseeding or Overseeding

Interseeding or overseeding of cover crops into a standing cash crop can eliminate the empty niche following harvest. Red, white, crimson, and subterranean clovers; Italian ryegrass; winter rye; and oats have sufficient shade- and traffic-tolerance to become established under the cash crop, then grow rapidly after it is harvested and cleared. Red clover is especially shade-tolerant with a “light compensation point” near 6% of full sun, so that its seedlings can become established even under a winter squash or pumpkin canopy. Combining a clover with a grass may fill the postharvest niche more thoroughly than either alone.

Some vegetable growers, especially those living in colder climates with short growing seasons, broadcast cover crops into established vegetables just before a final shallow cultivation to remove existing weeds and incorporate the cover crop seed. Essentially, this strategy utilizes the time after the vegetable crop’s minimum weed-free period to begin growing a cover crop in lieu of late-emerging weeds. Success depends on sufficient moisture and seed–soil contact to get the cover crop established.

Veteran vegetable grower and author Eliot Coleman has refined this approach, using a multirow push-seeder to drill cover crops between vegetable rows immediately after the final cultivation. Drilling can give better seed–soil contact, uniformity and stand establishment than broadcasting. Coleman (1995) developed an eight-year rotation for central Vermont (hardiness zone 4) that includes eight different vegetables, seven of them overseeded with various clovers and other cover crops (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Eliot Coleman, author of The New Organic Grower, uses a five-row push seeder to plant cover crops between rows of vegetables when the latter are at midgrowth. After vegetables are harvested and cleared away, the young clover cover crop rapidly covers the ground, effectively closing the niche between the vegetable and subsequent cover crop, while fixing nitrogen. Figure credits: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Grubinger (2004) has documented other successful cover crop overseeding practices used by organic farmers. Hank Bissell of Lewis Creek Farm in Starksboro, VT interseeds rye manually into fall brassicas to obtain winter and spring cover after the vegetables are finished. In early July, Will Stevens of Golden Russet Farm in Shoreham, VT seeds hairy vetch into winter squash. The vetch becomes established under the squash, covers the ground when frost kills squash foliage, and grows until the following May, thereby shutting out weeds while fixing a lot of nitrogen.

No-till Cover Crop Management

No-till cover crop management entails mowing or rolling a mature cover crop to create an in situ mulch, into which vegetable starts or large seeds can be planted. This eliminates the bare-soil period between a cover crop and the subsequent vegetable, as well as tillage-related stimuli to weed seed germination. Under favorable conditions, the mulch from a high-biomass cover crop can delay the onset of weed growth for four or more weeks after vegetable planting. However, results in terms of weed control and vegetable yield have been inconsistent. Additional research is needed to refine this technique and define circumstances in which it is most likely to succeed.

Living Mulch

Living mulch consists of one or more low-growing ground cover species—for example, low-growing legumes such as white Dutch clover; dwarf perennial ryegrass; and creeping red fescue—maintained between crop rows or beds by periodic mowing. The goal is to replace tall, competitive, hard-to-manage weeds with low-growing perennial vegetation that suppresses weeds and protects the soil, while having minimal impact on crop yield. This approach works well for woody perennial crops like blueberries, grapes, and orchard fruits. However, it has been found difficult to keep living mulches from reducing vegetable yields by competing for moisture or nutrients. Living mulch has been used successfully in alleys between plastic-mulched beds of either annual vegetables or perennial crops.

The living mulch and some of its variants remain subjects of experimentation by scientists and farmers. A dying mulch consists of a winter annual grain, such as rye, planted in early spring to suppress or supplant between-row or between-bed weeds in spring planted vegetables. As summer heat builds, the winter annual living mulch declines and dies back while the vegetables enter their rapid growth and maturation phases. Another form of dying mulch is a non-winter-hardy cover crop, such as oats or buckwheat, sown in mid to late summer ahead of fall garlic planting. When the cover crop frost-kills, it becomes mulch through which the garlic emerges at the end of winter. In Pennsylvania, organic vegetable farmers Anne and Eric Nordell plant garlic into standing oats + field peas in October, which later winter-kill to provide at least some of the mulch required to suppress spring weeds in the garlic.

Self-seeding Winter Annual Cover Crops

Certain varieties of winter annual cover crops like subterranean clover, crimson clover, bigflower vetch, and Italian ryegrass can be grown as self-seeding cover crops. The cover crop is allowed to set seed and die down naturally in late spring, then followed by warm-season vegetable crops. The seeds germinate in late summer under the vegetable, thus regenerating the cover crop for the following winter without the need for postharvest tillage and seedbed preparation. The cover crop seed must be sufficiently summer-dormant that it does not emerge too early and compete with the vegetable, yet must establish sufficient stands to outcompete fall weeds. Farmers Jean Mills and Carol Eichelberger use crimson clover and annual ryegrass as self-seeding cover crops for certain vegetables on their farm in Coker, Alabama (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. The crimson clover and Italian ryegrass growing beneath these fall broccoli emerged from seed shed by an earlier cover crop the preceding spring. Hot summer weather kept the seeds dormant until the onset of autumn, at which time the vegetable was sufficiently established so that the emerging ryegrss and clover did not compete significantly. The photo was taken November, 2005 at Jean Mills and Carol Eichelberger's Tuscaloosa CSA in Coker, AL. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Minimizing Weed Niches in Small and Larger Scale Vegetable Production

Farmers and gardeners have developed many site-specific strategies for closing off weed niches in annual vegetable cropping systems. The details depend on climate, soil conditions, weed flora, crops grown, available equipment, and scale of operation. Growers who have limited land area tend to use more labor-intensive approaches aimed at maximum year round production of desired crop plants, and can afford to do some hand weeding during crop production. Farmers working larger acreages seek labor-efficient means to reduce weed pressure prior to planting the vegetable crop, thus minimizing weed control labor during crop production.

Over the past 40 years, Alan Chadwick and John Jeavons pioneered and developed the BioIntensive Minifarming method for sustainable food production in communities with limited land, machinery, and financial resources. Biointensive minifarming aims to make maximal use of every square foot of land to produce either food or biomass (grass–legume cover crops) to use for mulch or making compost. This system is characterized by very tight crop rotations with 60% of the time in cover crops, close plant spacings, companion planting, and multiple cropping (Jeavons, 2006). While labor intensive, this approach is highly productive and leaves little space for weeds to invade or compete. The few weeds that do emerge are pulled manually before they set seed, and composted.

Eric and Anne Nordell, who manage a six-acre vegetable farm in Pennsylvania primarily with draft horses, have developed an approach to weed management that they call bioextensive. Their strategy is to "weed the soil, not the crop", and their crop rotations include only one market crop every two years (Nordell and Nordell, 2006). The rest of the rotation is devoted to two high-biomass, weed-excluding cover crops, separated by a brief (4–6 week) cultivated fallow during the nonproduction season to draw down weed seed populations. Timing of fallow, cultivation implements (all horse-drawn), and methods are adjusted according to the existing weed flora—very shallow for small-seeded annuals; deeper for quack grass, dandelion, and other perennials. In the production year, the final cover crop is shallow-incorporated (minimizing tillage depth to reduce weed seed germination) a few weeks before vegetable planting. The Nordells find that this system greatly reduces weed control labor during vegetable production.

Another approach used on farms with sufficient land is to follow several years of intensive annual cropping with one to three full years under a perennial sod cover crop, such as red clover–timothy–orchardgrass. The perennial covers are planted, sometimes with a nurse crop of oats or other cereal grain, either after a vegetable harvest, or as an overseed into a standing vegetable crop. In addition to rebuilding the soil, the perennial cover effectively closes the niche for annual weeds-of-cultivation like lambsquarters and pigweeds, so that they cannot reproduce, and their weed seed bank declines through seed predation and decay. View the followng video clips for some ingenious and effective uses of perennial cover crops to build fertility and reduce weeds in organic vegetable production:

This article is part of a series on Twelve Steps Toward Ecological Weed Management in Organic Vegetables. For more information on cultural practices that reduce the niche for weeds, see:

- Grow Vigorous, Competitive Crops—the First Line of Defense Against Weeds

- Put the Weeds Out of Work—Grow Cover Crops!

- Plant and Manage Cover Crops for Maximum Weed Suppression

- What is “Organic No-till,” and Is It Practical?

- Video: Weed 'Em and Reap Part 2. Reduced Tillage Strategies for Vegetable Cropping Systems

References and Citations

- Coleman, E. 1995. The new organic grower: A master's manual of tools and techniques for the home and market gardener. 2nd ed. Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, VT.

- Grubinger, V. 2004. Farmers and their innovative cover cropping techniques [VHS tape/DVD]. University of Vermont Extension, Burlington, VT.

- Jeavons, J. 2006. How to grow more vegetables and fruits, nuts, berries, grains and other crops than you ever thought possible on less land than you can imagine. 7th edition. Ten Speed Press, Berkley, CA.

- Nordell, E., and A. Nordell. 2006. Weed the soil, not the crop: A whole-farm approach to the weed-free market garden. Small Farmer's Journal 30 (3 - summer): 53–58.

- Schonbeck, M., and R. Morse. 2007. Reduced tillage and cover cropping systems for organic vegetable production. Virginia Association for Biological Farming information sheet No. 9-07. (Available online at: http://vabf.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/reducedtillage_sm.pdf) (verified 4 May 2018).